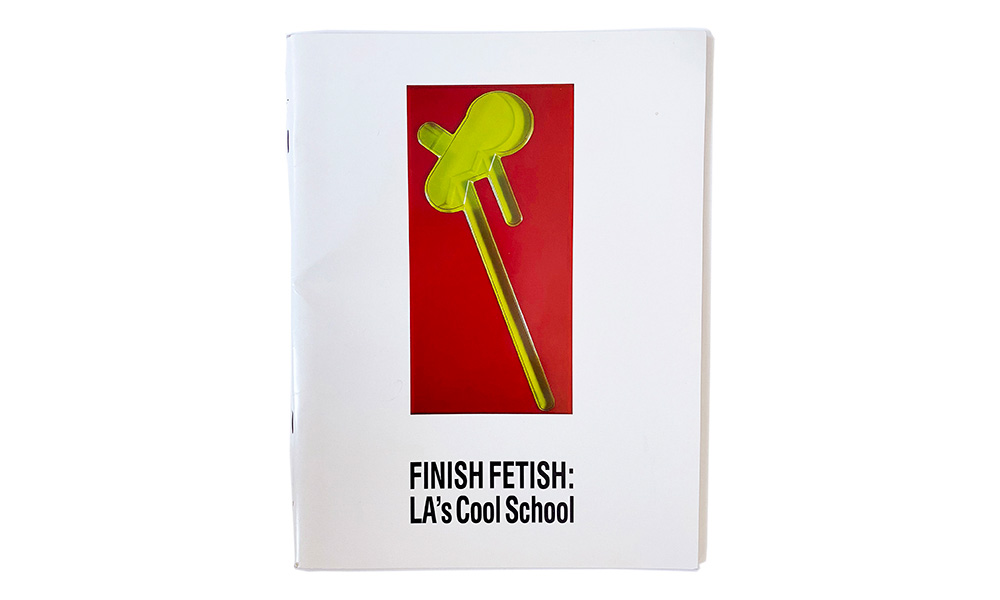

Finish Fetish 1991

Craig Kauffman’s elongated, silvery-pink bubble, made from vacuum-formed and spray-painted acrylic and dating from 1967-68, is the single most beautiful work in the exhibition “Finish Fetish: L.A.’s Cool School” at USC’s Fisher Gallery. Hung horizontally on the wall in the manner of a sculptural relief, the big, tumescent, lozenge-shaped form reeks of an androgynous sexiness.

Perhaps “obscenely beautiful” is a more precise description of the slick, exquisitely machined object. Beckoning sensuously while remaining glamorously aloof and self-contained, Kauffman’s untitled, pearlescent plastic sculpture is a brilliantly abstracted ode to the particular erotics of our mass-culture era. Artistically, it’s a most unusual amalgam: Highly refined abstraction is alloyed to the raucous sensibility of Pop.

Because abstraction and Pop were mutually exclusive terms in the 1960s, such a wedding was no mean feat. If you subscribed to the notion that abstract art represented the highest achievement modern culture had attained, while Pop was just a wallow in the lowest gutter of commercial display, the two could even be described as warring factions. The riveting liveliness of Kauffman’s sexy bubble lies in its seamless fusion of these apparently contradictory impulses.

Would Kauffman’s plastic reliefs of the 1960s therefore best be described as Abstract Pop? The term won’t be found in writings from or about the period, but it seems appropriate. Abstract Pop appears to describe essential qualities of the lacquered and polished planks by John McCracken, too, as well as of the garishly colored and erotically suggestive sculptures by DeWain Valentine, the cast resin bibelots by Helen Pashgian and Frederick Eversley, the etched and coated glass boxes of Larry Bell and several others in the show. All conceive of the work of art in the same general way: as a highly aestheticized form of the mass-produced object.

In fact, the oxymoronic fusion implied by Abstract Pop emerges as–quite possibly–a central characteristic of the genre that has been called, from the start, “finish fetish” art. I’m hedging on a flat-out assertion for two reasons. One is that the USC show is far too small to allow for a thorough consideration. (Neither do local museums offer much depth in their permanent collection displays.) The other is that no real effort to rethink the period emerges from the exhibition. Instead, it rehearses the standard litany of “Cool School” ingredients: surf boards, motorcycles, custom cars, Sunset Strip glamour, West Coast freedom from restrictive traditions and so on, which conspired to inflect the form this exquisitely flashy art would take.

It isn’t that these and other aspects of the 1960s milieu aren’t accurate to the period or germane to the art. We’ve just heard them all before. That the litany is now being rehearsed, a full generation later, inside the groves of academe certainly puts a loopy spin on the recitation. For, typically, champions of the “finish fetish” aesthetic cultivated a hip, sensual pose of anti-intellectualism. The Cool School offered a usefully stark, defining contrast to the highly intellectualized, often theoretically abstruse milieu that had grown up around the New York School.

To get a sense of how sharp the contrast was, try going straight from Fisher Gallery to the Museum of Contemporary Art and the sprawling exhibition of contemporaneous work, “The New Sculpture, 1965–75.” The throw-away grittiness of the latter, most of which was made by artists working in New York, is light years from the sparkling preciousness of the former. And to get a sense of how this contrast has nothing whatever to do with intrinsic regional differences between Los Angeles and New York, look especially at Bruce Nauman’s extraordinary work in “The New Sculpture.” Dating from exactly the years surveyed in “Finish Fetish,” virtually all of it was made while Nauman was living in L.A.

The USC exhibition–continuing through Saturday–includes just 21 works by 13 artists. Organized by graduate students in a museum studies class under the tutelage of Dr. Frances Colpitt, “Finish Fetish: L.A.’s Cool School” concentrates its tight focus on the second half of the 1960s. Billy Al Bengston’s spray lacquer and oil painting on cheap Masonite, “Zachary, ” is slightly earlier–it dates from 1961–and cast or coated resin sculptures in geometric forms by Eversley, McCracken and Peter Alexander slip into the early 1970s. The rest, however, are of the late ‘60s.

Bengston’s awkward “Zachary” is not a distinguished painting, but it does serve an illustrative purpose: Fabricated from polymer, lacquer and Masonite–materials more common to the machine shop than to the traditional artist’s studio–“Zachary” announces an art whose roots lie as deeply within the everyday world of man-made objects as within the formal history of painting and sculpture. Industrial techniques for painting motorcycles were transfered to the realm of art.

This is an important signal for understanding much of the painting and sculpture produced in Los Angeles during the 1960s. Bell etched and mirrored small glass boxes. Ron Davis molded polyester resin on fiberglass. Judy Gerowitz (who would soon change her last name to Chicago, the city of her birth) sandwiched air-brushed paint between clear and white acrylic sheets. Tony Delap coated sinuous forms of wood and fiberglass with lacquer. Robert Irwin cast acrylic and coated it with acrylic paint. Valentine fabricated large, decidedly vulgar forms of fiberglass reinforced polyester. (Imagine the mating of a flying saucer and an inflatable sex-doll and you’ll get some of the outlandish flavor of his 1967 “Pink Top” and “Yellow Roller.”)

The slim catalogue accompanying the USC show includes a brief but interesting essay on the history of plastic as an industrial material important to L.A.’s modern economy. It was relatively new to art (there are precedents, chiefly in the Bauhaus), but since the material was ubiquitous, a widespread attraction to various kinds of plastic is unsurprising. And the artists weren’t sending their designs out to factories to be fabricated; instead, factory methods were being adapted to the “small business” enterprise of making art. Studio practice remained paramount.

In a larger sense, the idea of using popular materials like plastic to make art is as old and venerable as collage. In Los Angeles, the most profound and far-reaching episode of such a reversal had occurred in the 1950s. Clay, which had been important to the commercial production of pottery in Southern California since before the turn of the century, suddenly became a principal sculptural medium in the hands of a number of artists affiliated with the Otis Art Institute.

Two small ceramic sculptures by Kenneth Price are included in the USC show. Price did use sprayed lacquer instead of ceramic glaze on several clay sculptures from the period, but the clay seems a bit anomalous amid all the plastic. Still, its presence suggests a provocative connection between ‘50s Otis Clay and ‘60s Abstract Pop.

Against a backdrop of new, industrial applications being tested for ceramic technology, remarkable ceramic sculpture was produced at Otis. Eventually, the school’s conservative administration decided to downplay ceramic sculpture in its curriculum and to emphasize clay as an applied art, useful in the burgeoning aerospace and building industries. If what I’m calling Abstract Pop is indeed an aestheticized form of the mass-produced object, its legacy from this slightly earlier episode seems undeniable. After all, Price, Bengston, Irwin and many other artists were connected to Otis during its ceramic sculpture heyday.

“Finish Fetish” is provocative, raising lots of such potentially fecund questions. But this little show barely scratches the surface. No substantive exhibitions of the period loom anywhere on the horizon and, given the near-total absence of publishing about art made in Los Angeles, there’s no reason to expect the arrival of insightful writing.

Significantly, it is in art dating from the past half-dozen years by a younger generation of artists that this impacted terrain is finally being pried open. Tim Ebner, Michael Gonzalez, Sarah Seager–who coincidentally had concurrent gallery shows in March–are three whose very diverse work is unthinkable without the precedent of ‘60s art in Los Angeles. Their work arises, at least in part, from a critical relationship to the legend-encrusted ancestors of Abstract Pop. Someday, perhaps institutional interest and challenge will follow their insightful lead.

VIA Los Angeles Times