Seyed Alavi: Canticles of Ecstasy 1998

For Seyed Alavi, creating objects and asking questions are equally important in his art-making process. For nearly two decades, the Bay Area artist has been working with public institutions to create conceptual works of art to be experienced by passersby. Spark follows Alavi as he offers a guided tour of his art and working process.

Though Alavi produces tangible objects, he thinks of himself as a conceptual artist, that is, the ideas behind his works are centralized over the finished object. Whereas many artists choose to master a specific medium and explore multiple subjects through it, Alavi works in several media. He develops a concept, plans the work for a specific location, then outsources the actual fabrication of the piece.

Alavi has created some of his most penetrating works with the help of high school students. His first such project was a series of text pieces painted under the overpasses of Interstate 580 in Oakland. Collaborating with a group of students from the region, he helped them to develop wordplays that would cause those who viewed them to think about the topics raised. Stenciled in capitalized serif fonts, the murals provocatively announce “INVISIBLE COLORS,” “INFORM(N)ATION,” and “D FFERENCE,” the last suggesting that one needs to include his or her “I” to make the “difference.”

Another project done in collaboration with students is a series of variations on the ubiquitous schematized human figures found on street signs. Together with a team of students, Alavi came up with 17 surreal alterations of the figures. They then painted their versions onto utility boxes scattered throughout the town of Emeryville, Calif., in order to raise questions about the nature of human identity, interaction and existence.

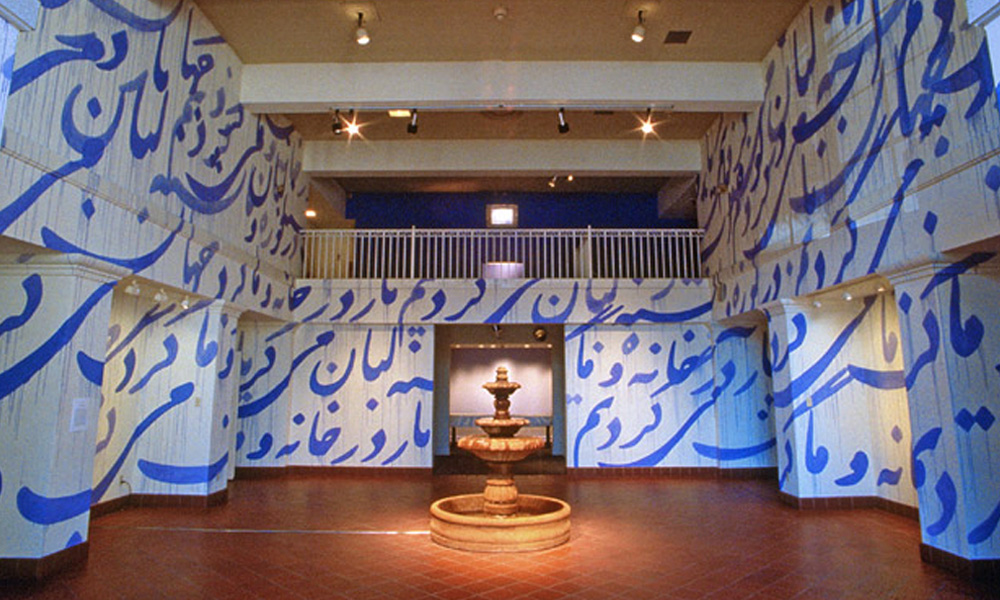

“Despite its theme, installation artist Seyed Alavi’s new show, Canticles of Ecstasy, is not intended to trigger an approximation of rapturous transport but rather tranquil contemplation of the ecstatic experience. The beauty of these pieces is more akin to a high-level chess game: cleverly conceived and smoothly accomplished with the greatest possible economy.

Seeking inspiration from the site, Alavi began to research the namesake of the university the de Saisset Museum calls home, Saint Clare. This led him to her mentor, St. Francis of Assisi, and on to other mystics.

This background research coalesced with Alavi’s own interest in Sufi mysticism, his Iranian heritage and the museum architecture. The combination works most effectively in the foyer installation: Searching. The two-story walls are completely covered with outsized Farsi script quoting from a poem by an anonymous 14th-century Sufi. Even before one turns toward the stairway to find the translation framed in projected light, the watery drips running from each letter convey an urgency bordering on obsession.”

– Ann Elliott Sherman